CS259 - Formal Languages

An alphabet is a non-empty finite set of symbols, denoted $\Sigma$. A language is a potentially infinite set of finite strings over and alphabet. $\Sigma^\star$ is the set of all finite strings (also called words) over the alphabet $\Sigma$.

Every decision problem can be phrased in the form "is a given string present in the language $L$?"

Deterministic finite automata

A deterministic finite automaton (DFA) / finite state machine (FSM), $M$ consists of a finite set of states, $Q$, a finite alphabet state $\Sigma$, a starting state $q_0 \in Q$, the final/accepting states, $F \subseteq Q$ and a transition function from one state to another, $\delta: Q \times \Sigma \rightarrow Q$, so $M = (Q, \Sigma, q_0, F, \delta)$.

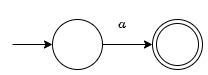

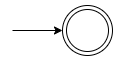

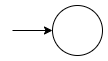

DFAs can be represented using a state transition diagram or state transition table. Circles on the state transition diagram are states. Double circles are accepting states. Arrows represent the transition function. A state transition table shows the mapping ($\delta$) of states and symbols to states. Final state will be labelled with an asterisk.

The empty string is denoted $\epsilon$.

The length of $\epsilon$ is 0, $|\epsilon| = 0$. $L_1 = \{\}$ is the empty language, $L_2 = \{\epsilon\}$ is a non-empty language. $\Sigma^\star$ always contains $\epsilon$.

Monoids comprise of a set, an associative binary operation ((<>) in Haskell) on the set and an identity element (mempty in Haskell).

The following are examples of monoids:

- $(\mathbb{N}_0, +, 0)$

- $(\mathbb{N}, \times, 1)$

- $(\Sigma^\star, \circ, \epsilon)$, where $\circ$ is string concatenation

The transition function of a DFA expresses the change in state upon reading a single symbol, $\delta(q_1, 0) = q_2$, for example. An extended transition function expresses the change in state upon reading a string, denoted $\hat{\delta}(q_1, 0011) = q_1$ (note the hat on $\delta$).

Formally, the extended transition function $\hat{\delta}: Q \times \Sigma^\star \rightarrow Q$ is defined inductively as

- For every $q \in Q$, $\hat{\delta}(q, \epsilon) = q$

- For every $q \in Q$ and word $s \in \Sigma^\star$ such that $s = wa$ for some $w \in \Sigma^\star$ and $a \in \Sigma$, $\hat{\delta}(q,s) = \delta(\hat{\delta}(q,w),a)$

The language accepted or recognised by a DFA, $M$, is denoted by $L(M) = \{s \in \Sigma^\star\;|\;\hat{\delta}(q_0, s) \in F\}$.

The run of a DFA, $M$, on a string is the sequence of states that the machine encounters when reading the string. The run of $M$ on $\epsilon$ is $q_0$. The run of $M$ on the word $s$ is a sequence of states $r_0,r_1,...,r_n$ where $r_0 = q_0$ and $\forall i \leq n, r_i = \delta(r_{i-1}, s_i)$.

The run of $M$ on a word $s$ is called an accepting run if the last state in the run is an accepting state of $M$. A word $s$ is said to be accepted by $M$ if the run of $M$ on $s$ is an accepting run. A language can then be defined as $L(M) = \{s\in \Sigma^\star \;|\; \text{the run of } M \text{ on } s \text{ is an accepting run}\}$

Regular languages

A language $L$ is regular if it is accepted by some DFA.

Any set operation can be applied to languages as languages are just sets of strings.

If $M = (Q, \Sigma, q_0, F, \delta)$ is a DFA for L then $M' = (Q, \Sigma, q_0, Q \setminus F, \delta)$ is a DFA for the complement of L, denoted $\bar{L}$. Regular languages are closed under complementation.

Regular languages are closed under intersection. Consider two DFA, $M_1 = (Q_1, \Sigma_1, q_1, F_1, \delta_1)$ and $M_2 = (Q_2, \Sigma_2, q_2, F_2, \delta_2)$ the intersection automaton $M_3 = (Q, \Sigma, q, F, \delta)$ where $Q = Q_1 \times Q_2$, $q = (q_1, q_2)$ and $F = F_1 \times F_2$. For every $a \in \Sigma, x \in Q_1, y \in Q_2$, $\delta((x,y),a) = (\delta_1(x,a), \delta_2(y,a))$.

This can be denoted $L(M_3) = L(M_1) \cap L(M_2)$.

Regular languages are closed under union. Using the same example as for intersection everything is the same except $F = (F_1 \times Q_2) \cup (F_2 \times Q_1)$.

Regular languages are closed under set difference as for two regular languages $L_1$ and $L_2$, $L_1 \setminus L_2 = L_1 \cap \bar{L}_2$ and regular languages are closed under intersection and complementation.

In conclusion, regular languages are closed under

- union

- intersection

- concatenation

- complementation

- Kleene closure (the star operator)

Non-deterministic finite state automata

A DFA has exactly 1 transition state out of a state for each symbol in the alphabet. An NFA can have no or multiple transitions out of a state on reading the same symbol.

An NFA can be obtained by reversing the arrows on a DFA. The accepting state becomes the start state and the start the accepting. If there are multiple accepting states in a DFA then a new start state is added for the NFA which has an arrow to all accepting states with label $\epsilon$. For example, the DFA for all binary strings ending with 00 will be and NFA for all binary strings starting with 00.

An NFA, like a DFA, consists of $(Q, \Sigma, q_0, F, \delta)$. The transition function is of the form $\delta: Q \times (\Sigma \cup \{\epsilon\}) \rightarrow 2^Q$. The extended transition function for an NFA is $\hat{\delta}: Q \times \Sigma^\star \rightarrow 2^Q$ where $\hat{\delta}(q,w)$ is all the states in $Q$ to which there is a run from $q$ upon reading the string $w$.

The $\epsilon$-closure of a state, $\operatorname{ECLOSE}(q)$, denotes all states that can be reached from $q$ by following $\epsilon$ transitions alone.

The extended transition function, $\hat{\delta}$, of an NFA $(Q, \Sigma, q_0, F, \delta)$ is a function $\delta: Q \times \Sigma^\star \rightarrow 2^Q$ defined as $\hat{\delta}(q, \epsilon) = \operatorname{ECLOSE}(q)$ and for every $q \in Q$ and word $s \in \Sigma^\star$ such that $s = wa$ for some $w \in \Sigma^\star$ and $a \in \Sigma$, $\hat{\delta}(q,s) = \operatorname{ECLOSE}(\bigcup_{q'\in\hat{\delta}(q,w)}\hat{\delta}(q', a))$.

The language accepted by an NFA, $L(M)$, is defined as $L(M) = \{s \in \Sigma^\star \;:\; \hat{\delta}(q_0, s) \cap F \neq \emptyset\}$.

A run of $M$ on the word $s$ is a sequence of states $r_0, r_1, ..., r_n$ such that $r_0 = q_0$ and $\exists s_1, s_2, ..., s_n \in \Sigma \cup \{\epsilon\}$ such that $s = s_1s_2...s_n$ and $\forall i \in [n], r_i \in \delta(r_{i-1}, s_i)$.

The language accepted by an NFA can also be defined as $L(M) = \{s \in \Sigma^\star\;|\; \text{some run of } M \text{ on } s \text{ is an accepting run}\}$.

Subset construction

Let $(Q, \Sigma, q_0, F, \sigma)$ be an NFA to be determinised. Let $M = (Q_1, \Sigma, q_1, F_1, \delta_1)$ be the resulting DFA.

- $Q_1 = 2^Q$

- $q_1 = \operatorname{ECLOSE}(q_0)$

- $F_1 = \{X \subseteq Q \;|\; X \cap F \neq \emptyset\}$

- $\delta_1(X,a) = \bigcup_{x \in X} \operatorname{ECLOSE}(\delta(x,a)) = \{z \;|\; \text{for some } x \in X, z = \operatorname{ECLOSE}(\delta(x,a))\}$

Regular expressions

The language generated by a regular expression, $R$, is $L(R)$ and is defined as

- $L(R) = \{a\}$ if $R = a$ for some $a \in \Sigma$

- $L(R) = \{\epsilon\}$ if $R = \epsilon$

- $L(R) = \emptyset$ if $R = \emptyset$

- $L(R) = L(R_1) \cup L(R_2)$ if $R = R_1 + R_2$

- $L(R) = L(R_1) \cdot L(R_2)$ if $R = R_1 \cdot R_2$ (concatenation)

- $L(R) = (L(R_1))^\star$ if $R = {R_1}^\star$

The operator precedence from highest to lowest is $*$, concatenation, $+$.

A language is accepted by an NFA/DFA if and only if it is generated by a regular expression.

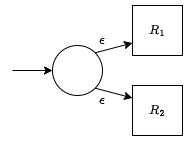

Regular expressions can be represented as NFAs.

The NFAs for the parts of regular expressions are

- $R = a$

- $R = \epsilon$

- $R = \emptyset$

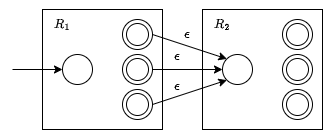

- $R = R_1 + R_2$

- $R = R_1 \cdot R_2$ - Epsilon transitions from all of the final states of $R_1$ to the start state of $R_2$.

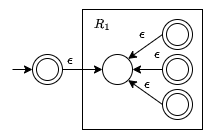

- $R = {R_1}^\star$ - Adds an initial accepting state because $R^\star$ accepts $\epsilon$ and adds epsilon transitions from the finishing states to the start state to represent multiple matches.

This method of converting regular expressions to NFAs is called Thompson's construction algorithm.

It is also possible to convert an NFA to a regular expression by eliminating state and replacing transitions with regular expressions.

Generalised NFAs

A GNFA is an NFA with regular expressions as transitions.

More formally, a generalised non-deterministic finite automaton (GNFA) is a 5-tuple $(Q, \Sigma, \delta, q_0, q_f)$ where

- $Q$ is the finite set of states

- $\Sigma$ is the input alphabet

- $\delta: (Q \setminus \{q_f\}) \times (Q \setminus \{q_0\}) \rightarrow R$ where $R$ is the set of all regular expressions over the alphabet

- $q_0$ is the start state

- $q_f$ is the accept state

For every $q \in Q \setminus \{q_0, q_f\}$:

- $q$ has outgoing arcs to all other states except $q_0$

- $q$ has incoming arcs from all other states except $q_f$

- $q$ has a self-loop

The run of a GNFA on a word $s \in \Sigma^\star$ is a sequence of states $r_0, r_1, ..., r_n$ such that $r_0 = q_0$ and $\exists s_1,s_2,...s_n \in \Sigma^\star$ such that $s = s_1s_2...s_n$ and $\forall i \in [n]$, $s_i \in L(\delta(r_{i-1}, r_i))$. The definition of accepting run and language are the same as usual.

Every NFA can be converted to an equivalent GNFA.

- Make a new unique start and final state for the NFA using $\epsilon$ transitions

- Add all possible missing transitions out of $q_0$ and into $q_f$ and into/out of all other states including self loops, all labelled $\emptyset$.

Non-regular languages

Non-regular languages can not be expressed using a finite number of states. Consider the extended transition function, $\hat{\delta}$. Starting at $q_0$, it is possible for multiple words to finish at the same end state, or alternatively $\hat{\delta}(q_0, s_1) = \hat{\delta}(q_0, s_2)$ for two strings $s_1$ and $s_2$. Words in a language can then be grouped based on their ending state and there will be a finite number of these groups (this is an equivalence relation and the groups are equivalence classes).

Strings $x$ and $y$ are distinguishable by a language $L$ if there is a string $z$ such that $xz \in L$ but $yz \notin L$ or vice versa. The string $z$ is said to distinguish $x$ and $y$.

If strings $x$ and $y$ are indistinguishable this can be denoted $x \equiv_L y$. $\equiv_L$ is an equivalence relation. The index of $\equiv_L$ is the number of equivalence classes of the relation.

If $L$ is a regular language then $\equiv_L$ has a finite index. Therefore is $\equiv_L$ has infinite index, $L$ must be non-regular.

Myhill-Nerode Theorem

$L$ is a regular language if and only if $\equiv_L$ has a finite index.

To prove a language $L$ is non-regular

- provide an infinite set of strings

- prove that they are pairwise distinguishable by L

This will prove that all strings lie in distinct equivalence classes of $\equiv_L$ and so $\equiv_L$ must have an infinite number of equivalence classes.

Example proof

The language $\{a^n,b^n,c^n\;|\;n\geq 0\}$ over $\{a, b,c\}$ is not regular.

- Consider the infinite set of strings generated by $a^\star$.

- For any $a^i$, $a^j$ where $i \neq j$, observe that $a^i \cdot a^{m-i}b^mc^m = a^mb^mc^m$, which is in $L$, while $a^j \cdot a^{m-i}b^mc^m \notin L$.

- This implies that the set of strings generated by $a^\star$ is pairwise distinguishable by $L$, and so $L$ has infinite index, implying that $L$ must be non-regular by the Myhill-Nerode theorem.

Pumping lemma

If there is a cycle that is reachable from the start state and which can reach an accept state in the state diagram of the DFA $M$ then $L(M)$ is infinite.

The Pumping Lemma

If $L$ is a regular language, then $\exists m>0$ such that $\forall w \in L$ such that $|w| \geq m$, there exists a decomposition $w = xyz$ such that $|y| > 0$, $|xy|\leq m$ such that $\forall i \geq 0$, $xy^iz \in L$.

A language $L$ is an irregular if $\forall m > 0$ such that $\exists w \in L$ such that $|w| \geq m$, such that for all decompositions of $w$ such that $|y| > 0$, $|xy|\leq m$ such that $\forall i \geq 0$, $xy^iz \in L$.

Proof using the pumping lemma follows 4 steps

- Suppose $L$ is regular and let $m$ be the pumping length of $L$

- Choose a string $w \in L$ such that $|w| \geq m$

- Let $w = xyz$ be an arbitrary decomposition of $w$ such that $|xy| \leq m$ and $|y| > 0$

- Carefully pick and integer $i$ and argue that $xyz \notin L$

Example proof

The language $\{a^nb^nc^n\;|\;n\geq 0\}$ over $\{a,b,c\}$ is not regular.

Let $L$ denote this language and for a contradiction, suppose that $L$ is regular and let $m$ be its pumping length. Let $w=a^mb^mc^m \in L$ and let $w = xyz$ where $|xy| \leq m$ and $|y| > 0$. Then $x = a^\alpha$, $y = a^\beta$ and $z = a^\gamma b^mc^m$ for some $\alpha$, $\beta$, $\gamma$ where $\alpha+\beta+\gamma = m$ and $\beta > 0$. Observe that $xy^0z = a^{\alpha + \gamma}b^mc^m$ where $\alpha + \gamma < m$ implying that $xy^0z \notin L$, a contradiction to the pumping lemma. This proves that $L$ is not regular.

Any regular language will satisfy the pumping lemma. A language which satisfies the pumping lemma is not necessarily regular. The pumping lemma can't be used to prove regularity but a regular language will satisfy the pumping lemma.

The pumping length of a regular language is the number of states in its equivalent DFA.

Grammars

A grammar can be denoted as $G = (V, \Sigma, R, S)$ where

- $V$ is a finite set of variables or non-terminals

- $\Sigma$ is a finite alphabet

- $R$ is a finite set of production rules or productions

- $S \in V$ is the start variable

Production rules are of the form $\alpha \rightarrow \beta$ where $\alpha, \beta \in (V \cup \Sigma)^\star$.

An example of a grammar is $G = (\{S\}, \{0,1\}, R, S)$ where $R$ is

- $S \rightarrow 0S1$

- $S \rightarrow \epsilon$

The string 000111 can be derived from the grammar $G$. $S \Rightarrow 0S1 \Rightarrow 00S11 \Rightarrow 000S111 \Rightarrow 000111$. This can be denoted more concisely as $S \overset{*}{\Rightarrow} 000111$.

For each step the string on the left yields the string on the right, so $0S1$ yields $00S11$.

More generally, for every $\alpha, \beta \in (V \cup \Sigma)^\star$ where $\alpha$ is non-empty

- $\alpha \Rightarrow \beta$ if $\alpha$ can be rewritten as $\beta$ by applying a production rule.

- $\alpha \overset{*}{\Rightarrow} \beta$ if $\alpha$ can be rewritten as $\beta$ by applying a finite number of production rules in succession.

The language of a grammar is defined as $L(G) = \{w \in \Sigma^\star \;|\; S \overset{*}{\Rightarrow} w\}$. This is the set of all strings in $\Sigma^\star$ that can be derived from $S$ using finitely many applications of the production rules in $G$.

The language of the example grammar above is $L(G) = \{0^n1^n \;|\;n \geq 0\}$.

The language of the grammar with $R: S \rightarrow S$ is the empty set, as there are no strings in $\Sigma^\star$ which can be derived from it.

A leftmost derivation is one in which successive derivations are first applied to the leftmost variable. A rightmost derivation is the opposite.

A parse tree can be used to represent a derivation. The start variable is the root node, then each variable derived from a production rule are the children.

A grammar is ambiguous if it can generate the same string with multiple parse trees. Equivalently, a grammar is ambiguous if the same string can be derived with two leftmost derivations.

Some ambiguous grammars can be rewritten as an equivalent unambiguous grammar. Those that can't are called inherently ambiguous. It is not possible to decide if a grammar is ambiguous.

Chomsky hierarchy of grammars

For some grammar $G$ where

- $V = \{A,B\}$

- $\alpha, \beta, \gamma, w \in (V \cup \Sigma)^\star$

- $x \in \Sigma^\star$

the hierarchy is

- Type 3: Regular right/left linear - Either $A \rightarrow xB$ and $A \rightarrow x$ (right) or $A \rightarrow Bx$ and $A \rightarrow x$ (left).

- Type 2: Context free - $A \rightarrow w$

- Type 1: Context sensitive - $\alpha A\gamma \rightarrow \alpha \beta \gamma$

- Type 0: Recursively enumerable - $\alpha \rightarrow \beta$

For a strictly regular language, $x \in \Sigma \cup \{\epsilon\}$.

Converting a DFA to a grammar

To convert a DFA to a grammar, let the variables be the states and the start variable be the start state. The rules are then the strings that will go to some accept state starting from each state.

More formally, given a DFA $M = (Q, \Sigma, q_0, F, \delta)$, the equivalent (strictly right-linear) grammar $G = (V, \Sigma, R, S)$ is given by $V = Q$, $S = q_0$ and $R:$

- $\forall q, q' \in Q, a \in \Sigma$ if $\delta(q,a) = q'$ then add rule $q \rightarrow aq'$

- $\forall q \in F$ add rule $q \rightarrow \epsilon$

If $\forall s \in \Sigma^\star$, $q \in Q$ then $\hat{\delta}(q,s) \in F$ if and only if $q \overset{\star}{\Rightarrow} s$. $s \in L(M)$ iff $\hat{\delta}(q_0, s) \in F$ iff $q_0 \overset{\star}{\Rightarrow} s$ iff $s \in L(G)$.

To generate a left-linear grammar, consider all strings from the start state to each state.

The same processes work for converting NFAs to right/left-linear grammars.

Pushdown automata

Context-free languages can't be generated by any of the methods seen so far. A pushdown automaton is a finite automaton with a stack which can generate context-free languages.

Formally, a pushdown automaton (PDA) is a 6-tuple $(Q, \Sigma, \Gamma, \delta, q_0, F)$ where $\Gamma$ is a finite state of the stack alphabet. It includes $\Sigma$ and usually the empty stack symbol, which is $. $\delta$ is defined as $\delta: Q \times \Sigma_\epsilon \times \Gamma_\epsilon \rightarrow 2^{Q \times \Gamma_\epsilon}$. By default, a PDA is non-deterministic.

Transitions in PDAs are denoted $a, c \rightarrow b$ which means read $a$, pop $c$ and push $b$ to move from one state to the next. Something is always read, popped and pushed, but it may be the empty string meaning no change. $b$ can be a string and the leftmost symbol will be on top of the stack.

Formally, the strings accepted by a PDA $(Q, \Sigma, \Gamma, \delta, q_0, F)$, $w \in \Sigma^\star$, must satisfy

- $\exists w_1, ...,w_r \in \Sigma \cup \{\epsilon\}$

- $\exists x_0, x_1, ... x_r \in Q$

- $\exists s_0, s_1, ..., s_r \in \Gamma^\star$

such that

- $w = w_1w_2...w_r$

- $x_0 = q_0$, $s_0 = \epsilon$

- $x_r \in F$

- $\forall i \in [r-1]$, $\delta(x_i, w_{i+1}, a) \ni (x_{i+1}, b)$ where $s_i = at$, $s_{i+1} = bt$ for some $a, b \in \Gamma \cup \{\epsilon\}$ and $t \in \Gamma^\star$.

The run of a PDA on a word $w = a_1...a_r$ is defined as a sequence $(q_0,s_0),...,(q_r,s_r)$ where

- each $q_i$ is a state of $M$

- each $s_i$ is a string over $\Gamma$

- $q_0$ is the start state of the automaton and $s_0$ is the empty string

- for every $i \in [r-1]$, there is a valid transition from $q_i$ with stack contents $s_i$ to $q_{i+1}$ with stack contents $s_{i+1}$ upon reading the symbol $a_{i+1}$.

A run is accepting if the last state in the sequence is accepting.

Pushdown automata accept precisely the set of context-free language. It can be proven that any pushdown automata can be converted to a context-free language and any context-free language can be converted to a pushdown automata.

Context-free grammar to PDA

The construction of a PDA from a CFG uses 3 states

- start state $q_s$

- loop state $q_l$ (simulates grammar rules)

- accept state $q_a$

Example

$G = (\{S\}, \{0,1\}, R, S)$ with $R:$

- $S \rightarrow 0S1$

- $S \rightarrow \epsilon$

The transition from $q_s$ to $q_l$ will be $\epsilon, \epsilon \rightarrow S$$.

The loop transitions will be

- $\epsilon, S \rightarrow 0S1$

- $\epsilon, S \rightarrow \epsilon$

- $0, 0 \rightarrow \epsilon$

- $1, 1 \rightarrow \epsilon$

The transition from $q_l$ to $q_a$ will be $\epsilon, $ \rightarrow \epsilon$.

PDA to CFG

A PDA needs to be normalised before it can be converted to a CFG. A normalised PDA

- has a single accept state

- empties its stack before accepting

- only has transitions that either push a symbol onto the stack (a push move) or pop one off the stack (a pop move) but does not do both at the same time.

To convert a normalised PDA to a CFG, create a variable $A_{pq}$ for each pair of states $p$ and $q$. $A_{pq}$ generates all strings that go from state $p$ with an empty stack to state $q$ with an empty stack.

The rules to generate CFG from a PDA are

- For each $p \in Q$ put the rule $A_{pp} \rightarrow \epsilon$ in $G$

- For each $p,q,r \in Q$ put the rule $A_{pq} \rightarrow A_{pr}A_{rq}$ in $G$

- For each $p,q,r,s \in Q$, $u \in \Gamma$ and $a,b \in \Sigma_\epsilon$ if $\delta(p,a,\epsilon)$ contains $(r,u)$ and $\delta(s,b,u)$ contains $(q, \epsilon)$ put the rule $A_{pq} \rightarrow aA_{rs}b$ in $G$.

CYK bottom up parsing for CFGs in Chomsky Normal Form

A grammar $G = (V, \Sigma, R, S)$ is in Chomsky Normal Form if every production has one of the following shapes:

- $S \rightarrow \epsilon$

- $A \rightarrow x$ ($x \in \Sigma$ is a terminal)

- $A \rightarrow BC$ ($B, C \in V$ where $B, C \neq S$)

The Cocke-Younger-Kasami (CYK) algorithm is a dynamic programming algorithm which builds a table of variables and substrings to work out if a string is generated by a CFG.

Consider a CFG $G = (V, \Sigma, R, S)$. Let $LHS(a) = \{J \in V \;|\; G \text{ has a rule } J \rightarrow a\}$. Let $w = y_1, y_2,...y_l$ and $w[1] = y_1, w[2] = y_2, w[l] = y_l$.

The algorithm is initialised with $M[1, i] = LHS(w[i]) \quad \forall i \in [l]$.

Let $LHS(P \times Q) = \{J \in V \;|\; G \text{ has a rule } J \rightarrow XY \text{ where } X \in P \text{ and } Y \in Q\}$.

The algorithm is then

for i = 2 to l

for j = 1 to l-(i-1)

for p = 1 to i-1

M[i,j] = M[i,j] ∪ LHS(M[p,j] × M[i-p, j+p])

$w$ can be derived from $G$ if and only if $M[l, 1]$ contains the start state $S$.

The time complexity of the algorithm is $O(n^3)$ where $n$ is the length of the string.

Converting to Chomsky normal form

Any context-free language is generated by a context-free grammar in Chomsky normal form.

A grammar $G = (V, \Sigma, R, S)$ can be converted to Chomsky normal form by doing the following

- Create a new start variable $S_0$ and add $S_0 \rightarrow S$

- Eliminate $A \rightarrow \epsilon$ productions where $A \neq S$

- Eliminate unit productions $A \rightarrow B$

- Add new variables and productions to eliminate remaining violations of the rules with more than two variables or two terminals.

Example

- $S \rightarrow ASB$

- $A \rightarrow aAS | a | \epsilon$

- $B \rightarrow SbS | A | bb$

- Add rule $S_0 \rightarrow S$

- For each rule with $A$, add a new rule with $A = \epsilon$ to eliminate $A \rightarrow \epsilon$. The rules are now

- $S_0 \rightarrow S$

- $S \rightarrow ASB | SB$

- $A \rightarrow aAS | a | aS$

- $B \rightarrow SbS | A | bb | \epsilon$

- This introduces $B \rightarrow \epsilon$ which can be removed the same way, giving

- $S_0 \rightarrow S$

- $S \rightarrow ASB | SB | AS | S$

- $A \rightarrow aAS | a | aS$

- $B \rightarrow SbS | A | bb$

- Eliminate unit productions. Firstly, replace $A$ with its RHS in the rule for $B$

- $S_0 \rightarrow S$

- $S \rightarrow ASB | SB | AS | S$

- $A \rightarrow aAS | a | aS$

- $B \rightarrow SbS | aAS | a | aS | bb$

- Eliminate $S \rightarrow S$ and replace the RHS of $S_0$ with $S$

- $S_0 \rightarrow ASB | SB | AS$

- $S \rightarrow ASB | SB | AS$

- $A \rightarrow aAS | a | aS$

- $B \rightarrow SbS | aAS | a | aS | bb$

- Eliminate RHS with more than 2 variables by creating new rules

- $S_0 \rightarrow AU_1 | SB | AS$

- $S \rightarrow AU_1 | SB | AS$

- $A \rightarrow aU_2 | a | aS$

- $B \rightarrow SU_3 | aU_2 | a | aS | bb$

- $U_1 \rightarrow SB$

- $U_2 \rightarrow AS$

- $U_3 \rightarrow bS$

- Replace terminal-variable rules with extra rules

- $S_0 \rightarrow AU_1 | SB | AS$

- $S \rightarrow AU_1 | SB | AS$

- $A \rightarrow V_1U_2 | a | V_1S$

- $B \rightarrow SU_3 | V_1U_2 | a | V_1S | V_2V_2$

- $U_1 \rightarrow SB$

- $U_2 \rightarrow AS$

- $U_3 \rightarrow V_2S$

- $V_1 \rightarrow a$

- $V_2 \rightarrow b$

- This grammar is now in Chomsky normal form

Advantages of having a CFG in Chomsky normal form:

- the CYK algorithm can be used to parse strings in polynomial time

- every string of length $n$ can be derived in exactly $2n-1$ steps

Testing is a CFG produces and empty language

To test if the language generated by a CFG is empty

- Find and mark all variables with a terminal or $\epsilon$ on the right hand side

- Mark any variable $A$ for which there is a production $A \rightarrow w$ where $w$ comprises of only marked variables and terminals.

- Repeat 2. until no new variables get marked.

- If $S$ is unmarked, the language is empty.

Proving a language is context-free

The pumping lemma can be used to prove a language is regular. A variation of the pumping lemma can be used to prove a language is context-free. If $L$ is a context-free language, then $\exists m > 0$ such that $\forall w \in L: |w| \geq m, \exists$ a decomposition $w=uvxyz$ such that $|vy|>0$, $|vxy| \leq m$, $\forall i \geq 0$, $uv^ixy^iz \in L$.

The pumping length for a CFL is $m = b^{|V| + 1}$ where $b$ is the longest right hand side of a rule in the grammar and $|V|$ is the number of variables.

To prove a language is not context-free, assume it is context-free and show a contradiction.

Example

$L = \{a^nb^nc^n \;|\; n>0\}$ is not a CFL.

Assume that $L$ is a CFL and $m$ be its pumping length. Since $|vxy|\leq m$ and $|vy|>0$ it follows that $|vxy|$ contains at least one symbol from $\{a, b, c\}$ and at most 2. So $uv^0xy^0z \notin L$ as the number of each type of symbol can't be equal. This contradicts the pumping lemma so $L$ is not a CFL.

Testing is a CFG is finite

If a grammar contains no strings of length longer than the pumping length $m$ the language is finite.

If a grammar contains a string of length longer than $m$ it contains a string of length at most $2m-1$.

To check if a CFG is finite, generate all strings of length $m < l < 2m$ and use the CYK algorithm to check if they can be generated by the grammar. If any string can is generated by the grammar then its language is infinite.

Closure properties for CFLs

Context-free languages are closed under

- union

- concatenation

- Kleene closure

Context-free languages are not closed under

- intersection

- complementation

The intersection of a CFL with a regular language is a CFL. Let $M_1 = (Q_1, \Sigma, q_1, F_1, \delta_1)$ and $M_2 = (Q_2, \Sigma, \Gamma, q_2, F_2, \delta_2)$. Define their intersection be denoted $M = (Q, \Sigma, \Gamma, q, F, S)$ where

- $Q = Q_1 \times Q_2$

- $q = (q_1, q_2)$

- $F = F_1 \times F_2$

- $\forall a \in \Sigma, b \in \Gamma, \alpha \in Q_1, \beta \in Q_2$ we have $\delta((\alpha, \beta), a, b) \ni ((\alpha', \beta'), c)$ where $(\beta', c) \in \delta_2(\beta, a, b)$ and $\alpha' = \alpha$ if $a = \epsilon$ and $\delta_1(\alpha, a)$ otherwise.

Turing machines

A Turing machine consists of an infinite memory tape and a reading head which points to an item in memory. The reading head can either be moved left or right.

Formally, a Turing machine is a 7-tuple $(Q, \Sigma, \Gamma, \delta, q_0, q_\text{accept}, q_\text{reject})$ where $Q, \Sigma, \Gamma$ are all finite sets and

- $Q$ is the set of states

- $\Sigma$ is the input alphabet not containing the blank symbol $\sqcup$

- $\Gamma$ is the tape alphabet $\sqcup \in \Gamma$ and $\Sigma \subseteq \Gamma$

- $\delta: Q \times \Gamma \rightarrow Q \times \Gamma \times \{L, R\}$ is the transition function

- $q_0 \in Q$ is the start state

- $q_\text{accept} \in Q$ is the accept state

- $q_\text{reject} \in Q$ is the reject state where $q_\text{reject} \neq q_\text{accept}$

The $\vdash$ symbol denotes the start of the tape.

Transitions in a Turing machine are denoted $a \rightarrow b, L$ which means if the symbol pointed to by the reading head is $a$ then replace it with $b$ and move the reading head left. The third symbol can also be $S$ for stay on the current symbol, which could be expressed using multiple $L/R$ transitions but is used for convenience.

Turing machine terminology

- The configuration of a Turing machine is a snapshot of what the machine looks like at any point. $X = (u,q,v)$ is a configuration where $q$ is the current state, $u$ is the contents of the tape up to $q$ and $v$ is the contents of the tape after and including $q$.

- Configuration $X$ yields configuration $Y$ if the Turing machine can legally go from $X$ to $Y$ in one step.

- The start configuration is $(\vdash, q_0, w)$

- The accepting configuration is $(u, q_\text{accept}, v)$

- The rejecting configuration is $(u, q_\text{reject}, v)$

- Accepting or rejecting configurations are called halting configurations

- The run of a Turing machine $M$ of a string $w$ is a sequence of configurations $C_1, ..., C_r$ such that $C_1$ is the start configuration and for $i$ from $1$ to $r-1$ configuration $C_i$ yields $C_{i+1}$

- An accepting run is a run in which the last configuration is an accepting configuration

- A Turing machine can either halt and reject, halt and accept or not halt for an input

- The language accepted by a Turing machine is the set of words that are accepted by the machine

- A language is Turing-recognisable if it is the language accepted by some Turing machine. These are also called recursively enumerable and are generated by Chomsky type-0 grammars.

- A Turing machine that halts is called a decider ot total Turing machine. For a decider/total Turing machine $M$, $L(M)$ is the language decided by $M$.

- A language is Turing decidable if it is the language accepted by some decider/total Turing machine.

Adding multiple tapes, multiple heads or using bidirectional infinite tapes does not increase the power of the Turing machine model. All of these features can be expressed using a single tape with a single head.

Enumeration machines or enumerators are Turing machines with a dedicated output tape. It consists of a finite set of states with a special enumeration tape, a read/write work tape and a write-only output tape. It always starts with a blank work tape.

When it enters an enumeration state, the word in the output tape is enumerated. The machine erases the output tape, sends the write-only head back to the start, leaves the work tape untouched and continues. The language of an enumerator is the set of words enumerated by the machine. A language is Turing recognisable if and only if it is enumerated by some enumerator. Therefore recursively enumerable is the same as Turing recognisable.

To convert a Turing machine $M$ to an enumerator, for each $i = 1, 2, 3, ...$, run $M$ for $i$ steps on each input $s_1, s_2, ..., s_i$ and if any computations accept, print out the corresponding $s_j$.

A universal turing machine $U$ takes as input the string "Enc(M)#w" and simulates machine $M$ on word $w$. The input string is also denoted $\left<M, w\right>$.

Halting and membership problems

The halting problem is defined as $HP = \{\left<M,x\right>\;|\;M \text{ halts on } x\}$.

The halting problem is Turing-recognisable as the universal Turing machine can be used to run $\left<M, x\right>$. The halting problem is not decidable and this can be proven by contradiction.

Consider an infinite matrix where each row is a binary-encoded Turing machine and the columns are input strings. Each cell contains either $L$ or $H$ if the machine either loops or halts on the input. This matrix should contain every Turing machine.

Suppose there is a decider $N$ for the halting problem, then we can construct a Turing machine which is not present in the matrix, a contradiction. On input $\left<M, x\right>$ the machine $N$ halts and accepts if it determines that $M$ halts on input $x$ or halts and rejects if it determines that $M$ does not halt on input $x$.

Consider a Turing machine $K$ which on input $y$ writes $\left<M_y, y\right>$ (this corresponds to the diagonal of the matrix) on the input tape and simulates the run of the string $\left<M_y, y\right>$ on $N$ and finally halts and accepts if $N$ rejects or goes into an infinite loop if $N$ accepts.

The output of $K$ is the opposite of $N$ on the original matrix. Therefore $K$ cannot exist in the original matrix, but this matrix contains every turing machine, a contradiction. Therefore the halting problem is undecidable.

The membership problem is defined as $MP = \{\left<M,x\right>\;|\;x \in L(M)\}$. The membership problem is Turing-recognisable as the universal Turing machine can be used to simulate it.

The membership problem is undecidable. Suppose the membership problem is decidable and let $N$ be a decider for it. It can be shown that $N$ can be used to construct a decider $K$ for the halting problem, which is a contradiction as we have shown the halting problem is undecidable.

Consider a Turing machine $K$ that on input $\left<M, x\right>$ constructs a new machine $M'$ obtained from $M$ by adding a new accept state to $M$ and making all incoming transitions to the old accept and reject states go to the new accept state. The machine then simulates $N$ on input $\left<M', x\right>$ and accepts if $N$ accepts. As $N$ is undecidable, the membership problem is also undecidable. This is a reduction from the halting problem to the membership problem to show undecidability.

Reductions

For $A \subseteq \Sigma^$, $B \subseteq \Delta^$, $\sigma: \Sigma^* \rightarrow \Delta^$ is called a (mapping) reduction from $A$ to $B$ if for all $x \in \Sigma^, x \in A \iff \sigma(x) \in B$ and $\sigma$ is a computable function.

$\sigma$ is a computable function if there is a decider that, on input $x$, halts with $\sigma(x)$ written on the tape.

Consider an instance of the halting problem $\left<M, x\right>$. Define a Turing machine $M_x'(y)$ such that $y$ is ignored and $M$ is simulated on input $x$. If $M$ halts then accept. This is a mapping reduction from the halting problem to the membership problem.

$\left<M, x\right> \in HP \iff \left<M'_x,x\right> \in MP$. This means that if there is a decider for the membership problem, there is a decider for the halting problem as well.

Using reductions, other problems can be proved undecidable

- $\epsilon$-acceptance = $\{\left<M\right> \;|\; \epsilon \in L(M)\}$

- $\exists$-acceptance = $\{\left<M\right> \;|\; L(M) \neq \emptyset\}$

- $\forall$-acceptance = $\{\left<M\right> \;|\; L(M) = \Sigma^*\}$

The same reduction as for the membership problem can be used for these three problems.

Therefore $\left<M, x\right> \in HP$ if and only if

- $\left<M'_x,x\right> \in MP$

- $\left<M'_x\right> \in \epsilon$-acceptance

- $\left<M'_x\right> \in \exists$-acceptance

- $\left<M'_x\right> \in \forall$-acceptance

As there does not exist a decider for the halting problem, none of these problems are decidable.

If $A \leq_mB$ and

- $B$ is decidable then $A$ is decidable

- $A$ is undecidable then $B$ is undecidable

- $B$ is Turing-recognisable then $A$ is Turing-recognisable

- $A$ is not Turing-recognisable then $B$ is not Turing-recognisable

A language is decidable if and only if $L$ and $\overline{L}$ are both Turing-recognisable.

Proof forwards: If $L$ is decidable, then $L$ is Turing-recognisable by definition. $\overline{L}$ is everything that is not accepted by the decider for $L$, so is itself decidable and therefore Turing-recognisable.

Proof backwards: If $L$ and $\overline{L}$ are both Turing-recognisable with recognisers $P$ and $Q$ then a decider $M$ will run both $P$ and $Q$ on the input $x$. If $P$ accepts then halt and accept, if $Q$ accepts then halt and reject. $M$ is a decider for $L$.

The complement of the halting problem is not Turing-recognisable because if it was, then the halting problem and its complement would be recognisable which by the theorem above would make the halting problem decidable, which it is not.

Closure properties of Turing-recognisable and decidable languages

Both Turing-recognisable and decidable languages are closed under

- union

- intersection

- Kleene closure

- concatenation

Decidable languages are closed under complementation but Turing-recognisable languages are not as seen with the complement of the halting problem.

Languages classes

Regular languages are a subset of context-free languages are a subset of decidable languages. Decidable languages are the intersection of Turing-recognisable and co-Turing-recognisable languages.

Coursework notes (not examinable)

The first two stages of compilation are lexical analysis and syntax analysis.

Lexical analysis breaks source code up into tokens, classifies them, reports lexical errors, builds the symbol table and passes tokens to the parser. The parser does syntax analysis. It uses the grammar of the language to build a parse tree and then an abstract syntax tree.

Some common types of token include keywords, whitespace, identifiers, constants, operators and delimiters.

JavaCC generates a left-to-right top-down parser.