Calculus

Differentiation

Intermediate value theorem

If $f:[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}$ is a continuous function and $f(a)$ and $f(b)$ have opposite signs then $f(c) = 0$ for some $c \in (a,b)$.

Example: There is a number $x$ with $x^{179} + \frac{163}{1+x^2}=119$.

Consider $f(0)$. $f(0) = 163 - 119 > 0$

$f(1) = 1+\frac{163}{2} - 119 < 0$

By the intermediate value theorem there is a root between 0 and 1.

Extreme value theorem

If $f:[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}$ is continuous then there are points $m,M \in [a,b]$ with $f(m) \leq f(x) \leq f(M)$ for all $x \in [a,b]$.

Differentiability

Let $f$ be a real-valued function defined in some open interval of $\mathbb{R}$ containing the point $a$. If the limit $\lim\limits_{x \to a} \frac{f(x)-f(a)}{x-a}$ or alternatively $\lim\limits_{h \to 0} \frac{f(a+h)-f(a)}{h}$ exists then we say $f$ is differentiable at $a$ and denote the value of the limit by $f'(a)$. A function is differentiable if it is differentiable at each point in its domain.

If $f$ is differentiable at $a$ then $f$ is continuous at $a$ (doesn't work the other way round).

Combination rules for derivatives

If $f$ and $g$ are differentiable then so is $f+g$ and $(f+g)' = f' + g'$, $\lambda f$ for any $\lambda \in \mathbb{R}$ and $(\lambda f)' = \lambda f'$, $fg$ and $(fg)'$ = $fg'+f'g$ and so is $f/g$, $(f/g)'$ and these equal $(f'g - fg')/(g^2)$.

Properties of differentiable functions

Partial derivatives

The partial derivative of a function $f(x,y)$ of two independent variables $x$ and $y$ is obtained by differentiating $f(x,y)$ with respect to one of the two variables while holding the other constant.

The partial derivative is denoted $\frac{\partial}{\partial x}$.

For example the partial derivative of $f(x, y) = x^3 - \sin xy$ with

respect to $x$ is

$\frac{\partial f(x,y)}{\partial x} = 3x^2 - y \cos xy$. The $y$ is just

treated as a constant.

Differentiating the same equation with respect to $y$ gives

$\frac{\partial f(x,y)}{\partial y} = -x \cos xy$. $x^3$ becomes $0$

because $x$ is constant.

It is possible to use partial differentiation with any number of variables.

The second partial derivative of $f(x,y)$ with respect to $x$ would be expressed as $\frac{\partial^2 f(x,y)}{\partial x^2} = \frac{\partial}{\partial x} \left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\right)$.

The order of partial differentiation does not matter.

Differentiation of functions defined by power series

If $\Sigma(a_nx^n)$ is a power series with radius of convergence $R$, and $f$ is the function defined by $f(x) = \sum\limits_{n=0}^\infty a_nx^n$, $-R < x < R$ then $f$ is differentiable and $f'(x) = \sum\limits_{n=1}^\infty na_nx^{n-1}$, $-R < x < R$.

Stationary points and points of inflection

A point $a$ where $f'(a)=0$ is called a stationary point of $f$. A stationary point is not necessarily a turning point. Where a stationary point is neither a local maximum or minimum it is called a point of inflection. There are also non-stationary points of inflection.

If $f$ is continuous on $[a,b]$ and differentiable on $(a,b)$ then to locate the maximum and minimum values of $f$ on $[a,b$ we need to consider only the value of $f$ a the stationary points and the end points $a$ and $b$.

The maximum and minimum of $f$ on $[-1,2]$ where $f(x) = x^3 - x$ are given by $f'(x) = 3x^2 - 1=0$. Solving this gives $x = \pm\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}$. These are the stationary points. Finding the values of the functions at the min, max and stationary points gives $0, \frac{2}{3\sqrt{3}}, \frac{-2}{3\sqrt{3}}$ and $6$. Therefore the maximum is 6 and the minimum is $\frac{-2}{3\sqrt{3}}$.

Rolle's theorem

If $f:[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}$ is continuous, is differentiable on $(a,b)$ and $f(a)=f(b)$ then there is a point $c \in (a,b)$ with $f'(c) = 0$.

Mean value theorem

If $f$ is continuous on $[a,b]$ and differentiable on $(a,b)$ then there is a $c\in(a,b)$ with $f'(c) = \frac{f(b)-f(a)}{b-a}$.

L'Hôpital's rule, implicit differentiation and differentiation of inverse function

Curve sketching

Tips:

-

Find the stationary points

-

Find the value of $f(x)$ at each stationary point

-

Find the nature of each stationary point using $f''(x)$

-

Find the values where $f(x) = 0$

-

Determine the behaviour as $x \to \infty$

L'Hôpital's rule

This is used to calculate $\lim\limits_{x \to a} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)}$ when $f(a) = 0 = g(a)$.

If $f$ and $g$ are differentiable and $g'(a) \neq 0$ then

$\frac{f(x)}{g(x)} = \frac{f(x)-0}{g(x)-0} = \frac{f(x) - f(a)}{g(x)-g(a)} = \frac{\frac{f(x)-f(a)}{x-a}}{\frac{g(x)-g(a)}{x-a}} \to \frac{f'(a)}{g'(a)}$.

Hence $\lim\limits_{x \to a} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)}$ exists and is equal to

$\lim\limits_{x \to a} \frac{f'(x)}{g'(x)}$.

Implicit differentiation

Same as A level.

Differentiation of inverse functions

If $f:[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}$ is a continuous injective function with range $C$ then the inverse function $f^{-1}:c \to [a,b]$ is also continuous.

Let $f : [a,b] \to \mathbb{R}$ be a continuous function. If $f$ is differentiable on $(a,b)$ and $f'(x)>0$ for all $x \in (a,b)$ or $f'(x) < 0$ for all $x \in (a,b)$ then $f$ has an inverse function $f^{-1}$ which is differentiable.

If $y=f(x)$, then $(f^{-1})'(y) = \frac{1}{f^{-1}(x)}$ or equivalently $\frac{dx}{dy} = \frac{1}{\frac{dy}{dx}}$.

Integration

$m_r$ is the greatest lower bound of the set

$\{f(x) | x_{r-1} \leq x \leq x_r\}$.

$M_r$ is the least upper bound of the set

$\{f(x) | x_{r-1} \leq x \leq x_r\}$.

Let $f:[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}$ be a bounded function. A partition of

$[a,b]$ is a set $P = \{x_0,x_1,...,x_n\}$ of points with

$a = x_0 < x_1 <... <x_n = b$.

$m_r \leq f(x) \leq M_r$ when $x_{r-1} \leq x \leq x_{r}$, so the area

of the graph between $x_{r-1}$ and $x_r$ lies between

$m_r(x_r - x_{r-1})$ and $M_r(x_r - x_{r-1})$.

For each partition there is an upper and lower sum, $L(f,P)$ and

$U(f,P)$. These represent upper and lower estimates of the area under

the graph.

If there is a unique number $A$ with $L(f,P) \leq A \leq U(f,P)$ for every partition $P$ of $[a,b]$ then $f$ is integrable over $[a,b]$. The definite integral of $f$ is denoted $A = \int_a^b f(x) dx$ or alternatively $A = \lim\limits_{n \to \infty} \sum\limits_{r=1}^{n} f(x_r)(x_r-x_{r-1})$.

Basic integrable functions

-

Any continuous function on $[a,b]$ is integrable over $[a,b]$.

-

Any function which is increasing over $[a,b]$ is integrable over $[a,b]$.

-

Any function which is decreasing over $[a,b]$ is integrable over $[a,b]$.

Properties of definite integrals

-

Sum rule - If $f$ and $g$ are integrable then so is $f+g$

-

Multiple rule - If $f$ is integrable and $\lambda \in \mathbb{R}$ then $\lambda f$ is integrable

-

If $f$ is integrable over $[a,c]$ and over $[c,b]$ then $f$ is also integrable over $[a,b]$

-

If $f(x) \leq g(x)$ for every $x \in [a,b]$ then the integral of $f(x)$ is less than the integral of $g(x)$ if both exist.

If $f$ is a positive function then the integral of $f$ over $[a,b]$

represents the area between the graph of $f$ and the $x$-axis between

$x=a$ and $x=b$.

For a general $f$ the integral represents the difference of the area

between the positive part of $f$ and the $x$-axis and the negative part.

First fundamental theorem of calculus

Let $f:[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}$ be integrable, and define

$F:[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}$ by $F(x) = \int_a^x f(t)dt$.

If $f$ is continuous at $c \in (a,b)$, then $F$ is differentiable at $c$

and $F'(c) = f(c)$.

Second fundamental theorem of calculus

Let $f:[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}$ be continuous and suppose $F$ is a differentiable function with $F' = f$, then $\int_a^b f(x)dx = [F(x)]^b_a$ where $[F(x)]_a^b$ denotes $F(b) - F(a)$.

If $\frac{d}{dx}F(x) = f(x)$ for all $x$ and $f$ is continuous then $\int f(x) dx = F(x) + c$ for some constant $c$.

Logarithmic and exponential functions

$\log x = \int_1^x \frac{1}{t} dt$ for $x>0$.

Since $\log:(0, \infty) \to \mathbb{R}$ is bijective, it has an inverse

function denoted by $\exp$. $y = \exp(x) \Leftrightarrow x = \log y$ and

$e = \exp(1)$.

Properties of the exponential functions

For any $x, y \in \mathbb{R}$:

-

$\exp(x+y) = \exp(x)\exp(y)$

-

$\exp$ is differentiable, $\frac{d}{dx}(\exp(x)) = \exp(x)$

-

$\exp(x) = \lim\limits_{n \to \infty}\left(1 + \frac{x}{n}\right)^n$

-

$\exp(x) = \sum\limits_{n = 0}^\infty \frac{x^n}{n!}$

$e^x = \exp(x)$ and $e^{x+y} = e^x e^y$ for any $x,y \in \mathbb{R}$.

For $a>0, x \in \mathbb{R}$, $a^x = e^{x \log a}$ and

$\log a^x = x \log a$.

$\log_b x = \frac{\log x}{\log b}, b \neq 1$. Using this, if

$y = \log_b x$ then $x = b^y$.

Taylor's theorem

Let $f$ be a $(n+1)$-times differentiable function on an open interval containing the points $a$ and $x$. Then

$$ f(x) = f(x) + f'(a)(x-a) + \frac{f''(a)}{2!}(x-a)^2 + ... + \frac{f^n(a)}{n!}(x-a)^n + R_n(x) $$

where $R_n(x)$ is defined as

$$ R_n(x) = \frac{f^{(n+1)}(c)}{(n+1)!}(x-a)^{n+1} $$ for some number $c$ between $a$ and $x$.

The function $T_n$ is defined by

$$ T_n(x) = a_0 + a_1(x-a) + a_2(x-a)^2 +...+ a_n(x-a)^n $$ where $a_r = \frac{f^r(a)}{r!}$. This is called the Taylor polynomial of degree $n$ of $f$ at $a$.

This polynomial approximates $f$ in some interval containing $a$. The error in the approximation is given by the remainder term $R_n(x)$.

If $R_n(x) \to 0$ as $n \to \infty$ then the sequence becomes a power series: $$ f(x) = \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{f^n(a)}{n!}(x-a)^n $$ This is the Taylor series for $f$.

$n$th derivative test for the nature of stationary points

Suppose that $f$ has a stationary point at $a$ and that $f'(a)=...=f^(n-1)(a)=0$, while $f^n(a) \neq 0$. If $f^n$ is a continuous function then

-

if $n$ is even and $f^n(a) > 0$ then $f$ has a local minimum at $a$

-

if $n$ is even and $f^n(a) < 0$ then $f$ has a local maximum at $a$

-

if $n$ is odd then $f$ has a point of inflection at $a$

Maclaurin series

This is a Taylor series where $a = 0$.

$$ f(x) = \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{f^n(0)}{n!}x^n $$ where $f^0(0) = f(0)$.

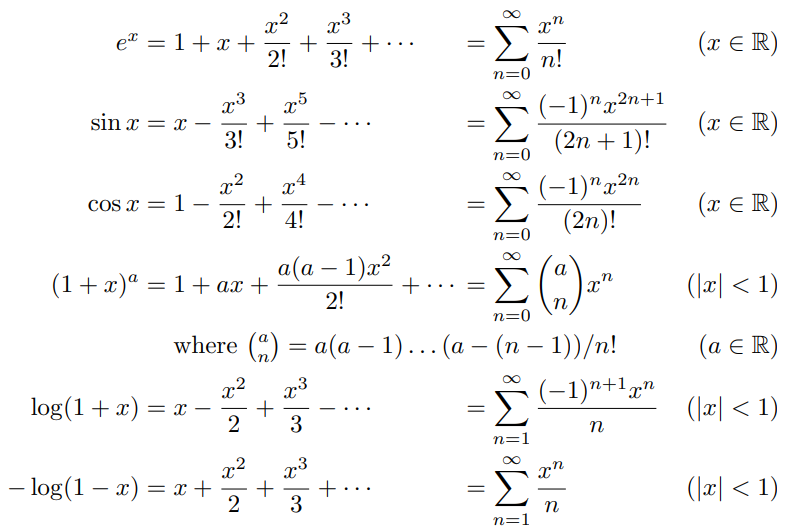

Common Maclaurin series

First order ordinary differential equations

An ordinary differential equation (ODE) is an equation which contains derivatives of a function of a single variable. The order is the highest derivative it contains.